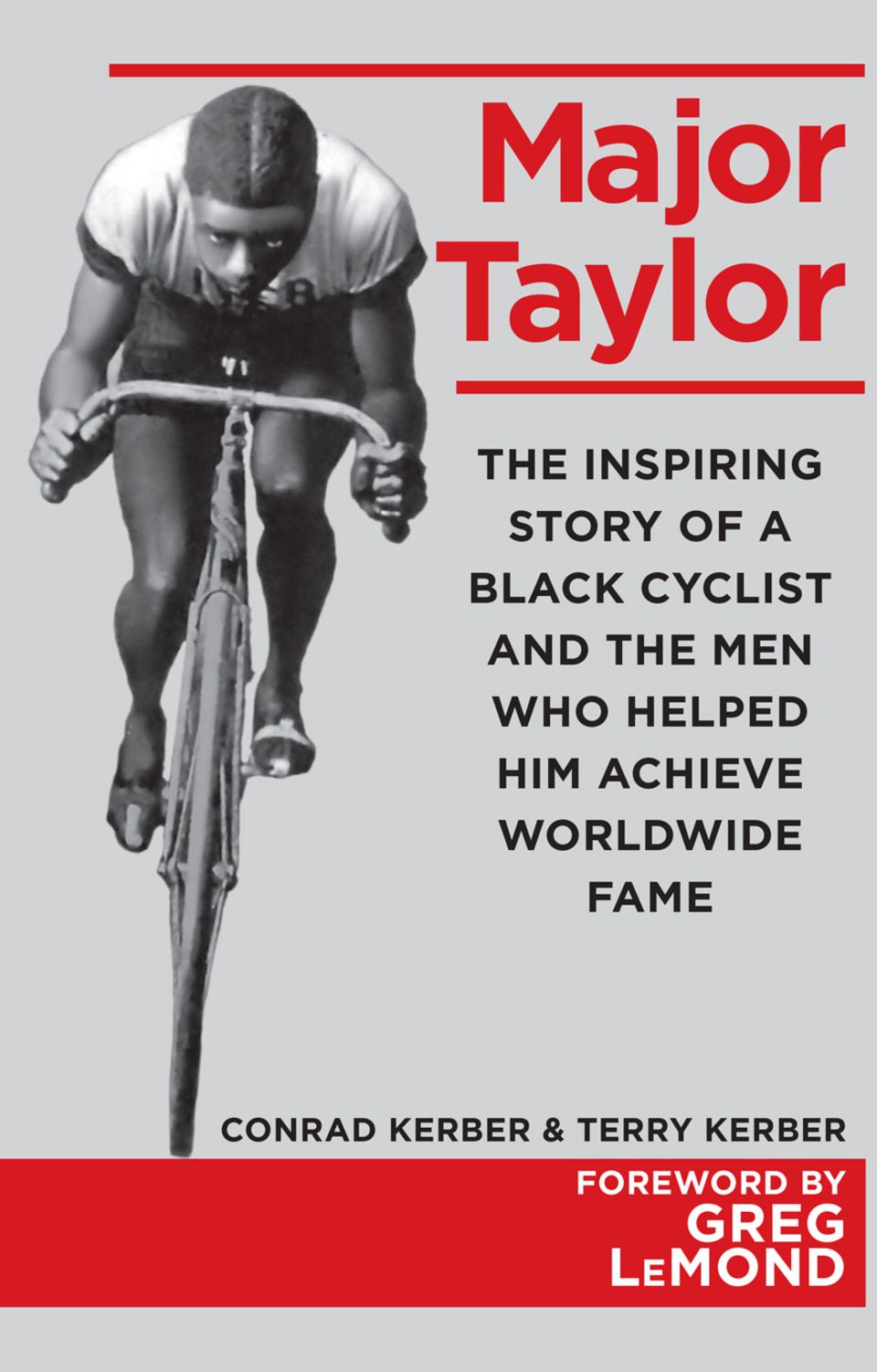

About Major Taylor

In 1907, amid a time of unspeakable racial cruelty, the world’s most popular athlete was not pitcher Cy Young or Christy Mathewson. It wasn’t shortstop Honus Wagner, center fielder Ty Cobb, nor was he a baseball player. During a period of frequent lynchings, the world’s most popular athlete wasn’t even white. He was an oft-persecuted, black bicycle racer named Marshall W. “Major” Taylor.

At the height of the Jim Crow era, Taylor became an inspirational idol in America, Europe, and Australia, experiencing adoration so profound that it transcended race. Long before Jackie Robinson, people of all colors passed under Major Taylor billboards, exchanged Taylor trading cards, cooled themselves with Taylor accordion fans, and wore buttons bearing his likeness. When he competed, his admirers swarmed local streets, spilled out of “Major Taylor Carnival” trains, flooded the cafés, and waited for him in the rain outside packed hotels. His face stared out from newspaper pages on four continents. His appearances shattered attendance records at nearly every bike track and drew the largest throng ever to see a sporting event. At a time when the population was less than one quarter its current size, more than fifty thousand people watched him race, a crowd on par with today’s baseball games. Countless thousands paid just to watch his workouts, while thousands of others gathered at train stations to greet him and his elegant wife.

But his immense fame, achieved in what was one of the nation’s most popular sports, came against incredible odds. He was repeatedly kicked out of restaurants and hotels, forced to sleep in horse stables, and terrorized out of cities by threats of violence. On the more than one hundred bike tracks called velodromes, he endured incessant racism, including being shoved head-first into track rails. On a sultry New England day in 1897, a rival nearly choked him to death, a violent incident the New York Times called among the most talked-about in sport.

Along his turbulent path that began as a penniless horse-tender from bucolic Indiana, Taylor received help from the most unlikely of men, all of whom happened to be white. When hotel and restaurant operators refused him food and lodging, forcing him to race hungry, a benevolent racer-turned-trainer named Birdie Munger took Taylor under his wing and into his home. One of Taylor’s managers was famed Broadway producer William Brady, a feisty Irishman who had brawled with Virgil Earp in cow-town boxing rings. He stood up for Taylor when track owners tried to bar him from competing. While winning more than one thousand bike races himself, Arthur Zimmerman, America’s first superstar, mentored Taylor even though others called him a useless little “pickanninny.” In the mid-1890s during a devastating depression, the extraordinary kindness these men bestowed helped elevate Taylor from rags to riches.

But for Taylor and his helpers, it was merely the start of a fourteen-year journey filled with suffering and jubilation. From 1896 to 1910, Taylor emerged as one of history’s most remarkable sportsman. Endowed with blazing speed and indomitable bravery, he traveled more than two hundred thousand grueling miles by rail and ship, started two-mile handicap races as far back as three hundred yards, and set numerous world speed records. His danger-filled struggle for equality on American tracks eventually drove him overseas where he became the most heavily advertised man in Europe, was talked about as often as presidents of countries, and captured more attention than some of the world’s wealthiest citizens. His dramatic match races with French Triple Crown winner Edmond Jacquelin, which attracted barons, dukes, and paupers from nearly every nation in Europe, were widely remembered a quarter-century later. And in 1907 after a fall instigated by an envious rival—a severe injury that led to a mental breakdown—the much-maligned black man attempted a comeback many thought impossible.

But it wasn’t just athletic greatness that attracted people to him. Carrying the Scriptures with him always, this deeply religious man turned down enormous sums of money because he refused to race on Sunday. Thousands were captivated by his eloquent, peaceful delivery of messages about faith and kindness, and his mystical capacity to forgive those who persecuted him.

During his ride from anonymity to superstardom, the gentle black man and the few white men who helped him starred in an epic story for the ages.

It began with two boys on bicycles, riding free.

At the height of the Jim Crow era, Taylor became an inspirational idol in America, Europe, and Australia, experiencing adoration so profound that it transcended race. Long before Jackie Robinson, people of all colors passed under Major Taylor billboards, exchanged Taylor trading cards, cooled themselves with Taylor accordion fans, and wore buttons bearing his likeness. When he competed, his admirers swarmed local streets, spilled out of “Major Taylor Carnival” trains, flooded the cafés, and waited for him in the rain outside packed hotels. His face stared out from newspaper pages on four continents. His appearances shattered attendance records at nearly every bike track and drew the largest throng ever to see a sporting event. At a time when the population was less than one quarter its current size, more than fifty thousand people watched him race, a crowd on par with today’s baseball games. Countless thousands paid just to watch his workouts, while thousands of others gathered at train stations to greet him and his elegant wife.

But his immense fame, achieved in what was one of the nation’s most popular sports, came against incredible odds. He was repeatedly kicked out of restaurants and hotels, forced to sleep in horse stables, and terrorized out of cities by threats of violence. On the more than one hundred bike tracks called velodromes, he endured incessant racism, including being shoved head-first into track rails. On a sultry New England day in 1897, a rival nearly choked him to death, a violent incident the New York Times called among the most talked-about in sport.

Along his turbulent path that began as a penniless horse-tender from bucolic Indiana, Taylor received help from the most unlikely of men, all of whom happened to be white. When hotel and restaurant operators refused him food and lodging, forcing him to race hungry, a benevolent racer-turned-trainer named Birdie Munger took Taylor under his wing and into his home. One of Taylor’s managers was famed Broadway producer William Brady, a feisty Irishman who had brawled with Virgil Earp in cow-town boxing rings. He stood up for Taylor when track owners tried to bar him from competing. While winning more than one thousand bike races himself, Arthur Zimmerman, America’s first superstar, mentored Taylor even though others called him a useless little “pickanninny.” In the mid-1890s during a devastating depression, the extraordinary kindness these men bestowed helped elevate Taylor from rags to riches.

But for Taylor and his helpers, it was merely the start of a fourteen-year journey filled with suffering and jubilation. From 1896 to 1910, Taylor emerged as one of history’s most remarkable sportsman. Endowed with blazing speed and indomitable bravery, he traveled more than two hundred thousand grueling miles by rail and ship, started two-mile handicap races as far back as three hundred yards, and set numerous world speed records. His danger-filled struggle for equality on American tracks eventually drove him overseas where he became the most heavily advertised man in Europe, was talked about as often as presidents of countries, and captured more attention than some of the world’s wealthiest citizens. His dramatic match races with French Triple Crown winner Edmond Jacquelin, which attracted barons, dukes, and paupers from nearly every nation in Europe, were widely remembered a quarter-century later. And in 1907 after a fall instigated by an envious rival—a severe injury that led to a mental breakdown—the much-maligned black man attempted a comeback many thought impossible.

But it wasn’t just athletic greatness that attracted people to him. Carrying the Scriptures with him always, this deeply religious man turned down enormous sums of money because he refused to race on Sunday. Thousands were captivated by his eloquent, peaceful delivery of messages about faith and kindness, and his mystical capacity to forgive those who persecuted him.

During his ride from anonymity to superstardom, the gentle black man and the few white men who helped him starred in an epic story for the ages.

It began with two boys on bicycles, riding free.